@Konidias: No problem

@ericmbernier: Thanks!

I’m terrible at updating, sorry. Too much code to write

We’re sending out the first playable builds to Alpha backers at this end of the month, so the time crunch is on to get some critical features of the game working. I’ve been writing this update for the last month; it’s long and kind of disjointed so I’ve broken it into segments.

GreenlightAs expected the last 2 months have seen very low traffic and, accordingly, low votes with all of our initial press dropping off. There have been a few small mentions on twitter or a blog here and there, but largely, I think the majority of our traffic lately has come from within Greenlight itself. Not terribly surprising is that our Yes/No ratio has been dropping in line with the general traffic; it suggests that our Yes/No is much, much lower from Greenlight generated traffic versus externally generated traffic. Our best sustained Yes/No was in the 0-15k Yes votes range at roughly 64/32, which leveled off around 56/42 but has fallen in the last month to 54/45.

Despite the low number of views, we’ve still been making some progress up the ranks - although that is largely due to games in front of us getting Greenlit.

I’ve not really had time to do any proper analysis, but looking at similar projects to ours (in terms of scope/quality and maybe genre) it seems like there are two necessary things for getting enough votes, assuming you are a relatively unknown studio and your game meets some level of subjective “good quality.”

1: Press

2: Public Demo

Examples: Legend of Dungeon, Hammerwatch, Papers Please, Rogue Legacy, Shovel Knight, Chasm (not Greenlit yet, but it has to be imminent), etc.

The one exception to the above is Shovel Knight which had no public demo (but was playable at PAX East.) Despite being a new team, all of them coming from WayForward might bump them out of the “relatively unknown” category.

We have received, what I think most indies would consider, a lot of press: most of the major game sites have covered us at some point since February and several big Youtubers (Northernlion, Epic Name Bro, TotalBiscuit) have put out a video on the game. On a disappointing note, our TotalBiscuit video had some kind of weird and really bad skip in the playback (that wasn’t occurring when he was playing) which probably hurt us a good deal with his audience. Even with all of that and showing at PAX East, we’ve only got 30k votes and are, by my reckoning, about 15k votes out of the top 10.

The good news is that the probable solution for us is a public demo - something we were going to do anyway. We’ll probably release the demo after we get into Beta a good bit, which should still give us enough time time to get the GL and release on Steam at launch (in late October.)

The Content PipelineWhen making a game of any sort of large scope, it’s impossible to understate how important having a really, really great content pipeline is. Every bit of friction between getting assets/data from their inception into the game can cause massive ripple effects that put undue stress and pressure on everyone. A broken pipe can literally kill a game.

Up until March, we had been using the following tools:

-In-house texture tool

-In-house frame by frame animation tool

-Tiled, although our integration was very thin

-Text editors for XML data used in our databases and scene files

Our internal tools were all very rough - basically accomplishing the bare minimum needed. The scope of DD necessitated that we had to improve our tools and our workflow or there would be no way we could finish by October.

Texture PackerOur texture tool needed a large overhaul - it had limited support for removing cells, combining textures, the interface was terrible, and it was PC only. Originally I planned on just adding the necessary features, doing some rework to the base code and calling it good. After estimating out the time needed and making a list of all of the features the artists wanted, it became apparent that an off-the-shelf solution would almost certainly be better. Enter

Texture Packer. I know that I had looked at TP at some point in the distant past, but couldn't remember the issues I had with it. After downloading the latest version and giving it a quick test ride, it was incredibly clear that we would be dumb to not use it. On top of that, the price tag ($30) is extremely tolerable, especially considering we needed multiple licenses.

Switching from our own texture format / tool to Texure Packer was a ton of work :/ On the game engine side, the code actually became much cleaner from an interface perspective if not slightly less optimal and wasn't particularly long to implement. Previously, our sprite format referenced a texture and the cells within it, but I wanted our artists to have as much flexibility as needed. I also expected that once we started heavy performance profiling we might want to reorganize our textures for batching improvements, so decoupling sprites from textures (just referencing cells) made a lot of sense. This is accomplished by doing a look-up at load time to cache the texture ID and the cell ID from the cell name; with a binary search the look-up times are negligible.

The majority of the work, however, stemmed from the fact that every asset in the game no longer worked and had to be updated, and the custom renderers (tilemaps, 9-sliced UI, 3D sprites/walls) required some rework. We made a new branch of the repo, removed all of the old assets (even for being relatively early in development, we already had several hundred sprite files) and slowly started adding things back in. Of course, not having the assets available meant we had to temporarily remove a lot of functionality and the result was maintaining both branches for a few weeks: prototype new features in the old branch and add/update the new art in the new branch and then merge once the game was working again with all of the new assets. This took even longer than we estimated because...

SpineNot only did we need to switch texture formats to accommodate using TP, we were also transitioning all of our animation from a frame by frame system to skeletal animation using Spine. Doing an HD 2D game, the biggest performance constraints you come up against are: fill rate and texture memory. Fill rate is a bigger problem on mobile devices and some older cards, but texture memory is a problem everywhere. The original plan was to do skeletal animation in Flash, then use a tool to convert the SWF/FLA data into some format more suitable for game use and voila. Alas, none of the converters that we found/tried actually exported our animations correctly and after looking into writing our own converter, realized that it’s actually quite difficult and would take a ton of time. So up until March, we’d been skeletally animating in Flash and then just exporting out frame by frame animations. We knew that to be an unsustainable solution - runtime memory usage, file size, animation limitations; it just wouldn’t work.

We had heard of Spriter during its Kickstarter and thought it would be a good solution for us. One of our artists animated a few different sprites in it to see how it works and came away pretty disappointed. The biggest issue was lack of features / poor work-flow and he effectively said it would take 2-3 times as long to animate in Spriter versus staying in Flash. It also seemed pretty buggy, so we were definitely having some second thoughts about using it, but it was still the best choice as far as I could see. Then, the heavens opened up and forth came

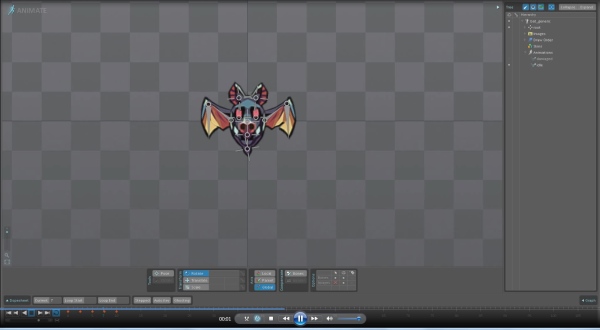

Spine. They were Kickstarting a variety of run-times for the tool and had a demo already available, so again we put an artist on it to get some animation running. After a few hours of work the result was in: Spine was awesome. Here’s a look at our generic bat inside the tool:

So the artists love Spine, great. Fortunately for me, one of the runtimes that was Kickstarted was a generic C-runtime. It took me a little bit to wrap my head around the structure of the SDK and its terminology, but after getting a general feel for it, it only took me about an hour to run into the first problem! It was a simple problem though - effectively I had to rewrite the AtlasAttachmentLoader module to work with our pre-existing resource management system. Apart from that, it worked straight out of the box; quite impressive. The way the animation system is set up for Spine objects (and the new-found things we could do like anim blending) required a substantial refactoring of how our internal animation handling code was set up, but really, the time spent getting Spine integrated into our engine was fairly minimal for results so glorious.

Of course, switching texture formats and animation formats at the same time on a game with a good number of assets was still not very pleasant and took up a ton of time. But to build the game correctly - to be 100% confident it will scale as we need - they were both very necessary steps and time well spent. Of course, there were even more pipeline changes....

TiledOn the plane ride to PAX Prime 2012, I whipped up an extremely basic tile mapping tool - it wasn’t meant to be permanent but we had extremely limited time to get a solution working. Once we started to plan out the game a bit more last fall, I added basic support for

Tiled. The artists, of course, love Tiled: its interface, features, everything, and implementing support for the TMX format was very trivial. Like all things, though, Tiled too had a dark side.

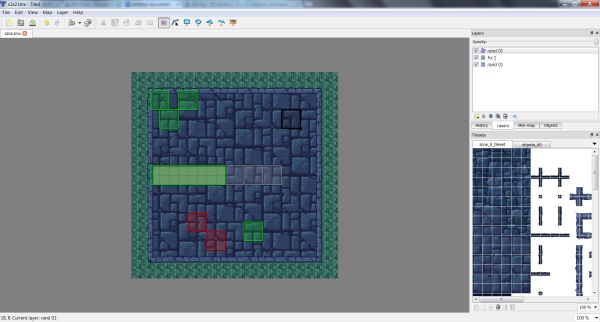

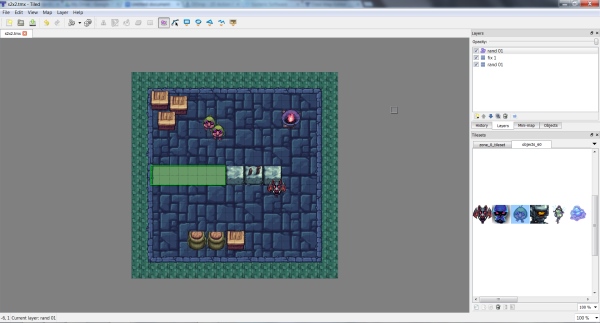

You want to make pretty tile maps with lots of layers? Tiled has got you covered. You want to place objects in your map as well? Tiled has got you partially covered. If you use non-tile based objects for your game, which is quite likely, Tiled does not have a WYSIWYG ability to do such. Rather, it supports the ability to draw arbitrary shapes as objects to which you can assign a “type” to - basically providing a type name and a color. Color coded shapes is not the worst thing in the world, but when you have a few hundred types of objects and an equal amount of maps, it is extremely difficult to open up a map file and understand it. Instead you have to right click on the objects to be able to check their type and thus figure out what is where and what is what.

We definitely needed something better than that so we decided to use and abuse the tile object system. Apart from the abstract object shapes, your other option is to import a tilesheet specifically for objects - which is perfect for truly tile based games and not so for games like ours. Fortunately, you can use as many tile sheets as you’d like in Tiled and you can set separate tile sizes for any given sheet, so we just ended up making a few object tilesheets of differing tile sizes and making simple icons by taking an appropriate sized screencap of the object. So while it is technically still not 100% WYISWYG due to us cropping basically every object a little bit, it is very close and definitely good enough to continue working with.

I also wanted to do some basic tests on large maps - although none of the rooms we have planned are particularly big, we will have a lot of them loaded at any given time and some of our outdoor areas might be on the larger side. I created a 1 million tile map (1000x1000) which Tiled seemed to handle reasonably well. The export, in the basic XML TMX format, was around 40 MB and the load time on my end was over 2 minutes. Not good. I had planned on supporting the base-64 zlib encoded format that Tiled can export but realized it was basically a requirement.

Before that, however, I profiled my XML parser as I was curious as to the reason for the terrible load times (other than just processing a lot of data.) I realized that a quick and easy optimization to my XML parser, would be to group sibling child nodes into arrays versus having one single array for all children. In cases where there were many siblings, look up time would be reduced to a binary search for the group name plus an array index - a vast improvement. The trade off is that for a file with virtually no siblings and many children, there is more memory consumption and slightly slower look up time. A reasonable trade imo. After implementing that change, load times went from over 2 minutes to ~20 seconds. Much better, but still not good enough.

Implementing a Base-64 encoder/decoder and the ZLib decompression took about twice as long as I expected, but the results were incredibly tasty: load time has been reduced to ~3 seconds and the file size was a mere 26 KB. Massive improvements in both cases and definitely good enough for me.

The final thing to support from Tiled, was the per instance properties that you can set. The format in which these are saved is not the most ideal (although perhaps the only way to remain truly generic) where each object gets a “properties” node that has a list of “property” nodes that have 2 key/value pairs: one for the prop name and the other for the value. Our current data format was set up so that properties are simply one key/value pair where the key is the actual prop name and that you can have as many props as attributes per node as you’d like. Adding in support for the Tiled way was simple enough, but it feels really dirty to have to separate property parsing methods in the game. Speaking of data...

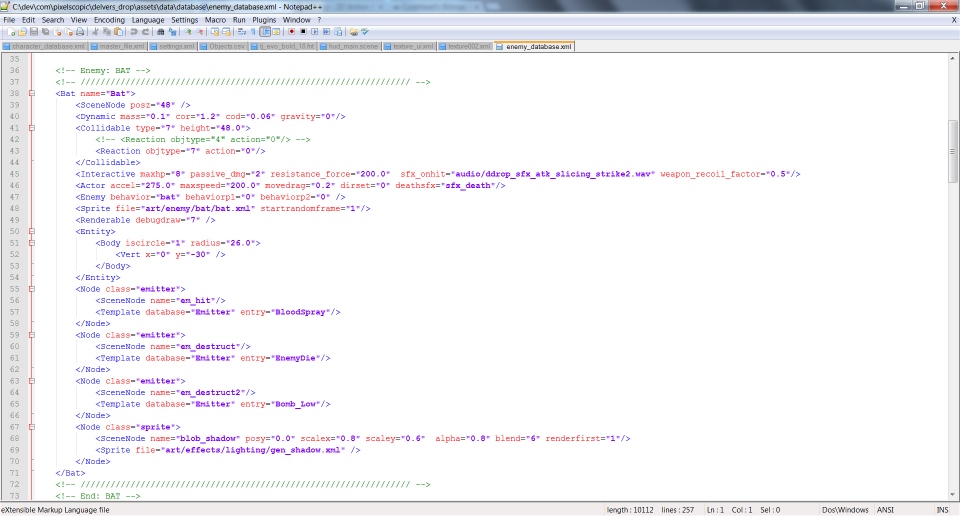

XML or CSVUp until last week we had been using XML to store both our game data and as the format for our scene files. It seemed to me to be really elegant and working quite well. Before I go on, I went back and forth over using binary serialization for smaller files / faster loads, but ultimately chose to go with a text based format for easy “live” editing and not wanting to deal with a conversion tool. Anyway, the happy XML times had slowly been eroding as we kept pumping more and more data into the game. Our main scripter/artist/designer was finding it more difficult and less efficient to use XML and was really pining for some better way. He was especially worried about when it came time to balance and fine-tune the game -- looking through tons of XML to look at value correlations between things seemed nightmare-ish.

Original Enemies Database (XML)

We had talked about perhaps using Excel (Google Spreadsheets) before and exporting as CSV to keep all of the data clear and coherent, but I was resistant to the idea since it would mean splitting our database and scene file structure apart and require two separate loading paradigms. Ultimately, however, editing massive quantities of XML by hand just no longer seemed feasible, so we decided to go for the CSV approach.

Fortunately I already had a CSV parser handy, so I refactored it a bit for this specific use case. On the code side, I had to go through and change the way that properties were parsed for all of our various game objects and components as well as restructure how references were handled. In the XML format, you could simply child an object under an object to have it instantiated whereas with the CSV, we have to put in a reference name that is looked up and created. Slightly more round about but not terrible. Switching the main data format, again, broke the hell out of the game. It took us quite some time to get the new spreadsheets set up and all of the old data ported over and tested. Ultimately though, I think this was a really smart decision, as editing the data and more importantly, quickly being able to view correlations and differences, is now much more friendly and fast.

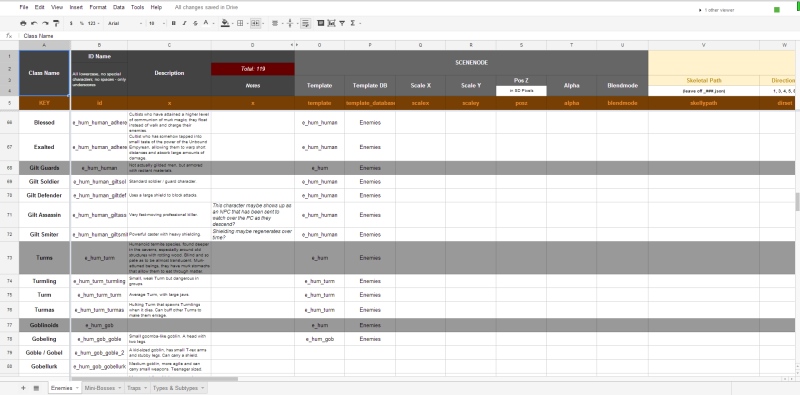

New Enemies Database (CSV)

BMFont

BMFontLast but not least, we switched our bitmap text format over from

Codehead’s Bitmap Font Generator to

BMFont. This was by far the easiest change to facilitate both code wise and asset wise (we only had 6 font files to convert over.) The primary reasons for the switch were the additional features that BMFont has as well as that BMFont exports out a packed texture. I’d been using CGFG for a really long time - as long as I can remember actually - but sometimes change is necessary

Summary

SummaryThe last 2 months have been breaking and rebuilding the foundations of the game/engine so that we avoid problems in the future as the scope of the game is realized. It’s been a sort of tedious two months, but at the same time, the road ahead now feels clear and clean. Exciting.

Community

Community DevLogs

DevLogs DDrop - 2D Action RPG

DDrop - 2D Action RPG Community

Community DevLogs

DevLogs DDrop - 2D Action RPG

DDrop - 2D Action RPG